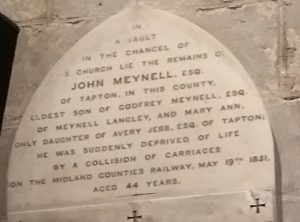

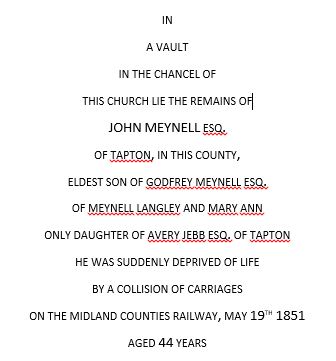

At a visit to St Michael’s church, Kirk Langley, in Derbyshire, I was intrigued by this sad memorial.

The Meynell family are well known in the area, having held land there since the reign of Henry I, and the church is full of their memorials. But what was the story behind the death of John Meynell?

According to the Leeds Intelligencer of the 24th May, John Meynell was travelling home with his wife on the London to Leeds train, which normally left London at 5pm.[1] The train was fifteen minutes late arriving at Derby, and it then stopped at Duffield, Belper, Ambergate and Wingfield. The stops at Duffield and Wingfield were unscheduled as technically the stations were already closed, and this caused a further delay. The train travelled through the Clay Cross tunnel at about 25 mph on an uphill stretch of line. Just after passing through Clay Cross station at the northern end of the tunnel the driver, John Sheldon, heard a noise and decided to stop the train (which took 200 yards to accomplish), telling the fireman, ‘Hold on! There’s something wrong here’.

Sheldon got down from the engine and diagnosed a broken pump rod, by which time the guard had walked from the rear of the train to find out what was wrong, and one or two passengers were looking out to find out why the train had stopped. The train crew all knew that there would be a goods train following the express, but it was not due at Chesterfield until fifty minutes after the passenger train. The express was due at Clay Cross at 9:41, and the ‘luggage train’ not until 10:31.

John Sheldon did not have any kind of watch or timepiece and usually calculated station arrival times according to experience and the speed they were doing, which usually averaged 30 mph.

The Clay Cross tunnel is 1,784-yard (1,631 m) long and there were signalmen at either end whose job it was to telegraph when a train had passed the signal box and to set the signals accordingly. There is a curve on the line after the tunnel at the northern end that meant the driver of the goods train had very little time to react to any signal as he emerged from the tunnel. Normal operating rules following an unscheduled stop would have led the guard of the passenger train to walk back down the line and set the nearest previous signal to danger, or to get the signalman to do so. However there was no-one on duty at night at Clay Cross station, nor enough time for the guard to walk back several hundred yards in the dark to set the signal himself before the driver called out that the problem was already fixed.

It had taken only a matter of four or five minutes for Sheldon to fix the problem, but as he was finishing and calling to the fireman to help pack up the tools and put them back in the tender, the fireman shouted ‘Jack, there is something coming into us’!

In the dark he could see the glow from the firebox of the approaching train. As Sheldon was hastily climbing back onto the engine and it was starting to move the following train crashed into the rear of the passenger express.

The heavy engine of the goods train smashed into the rear three carriages of the passenger train converting them instantly into matchwood. The first class carriage where the Meynells were sitting was at the rear of the train, and John Meynell, who had been looking out of the carriage window to see why the train had stopped, was thrown out onto his face and his legs were run over by the carriage wheels. He died instantly.

Several other passengers suffered severe injuries. A Mr Blake, a file manufacturer from Sheffield, died shortly afterwards while being taken to Chesterfield. John Todhunter of Dublin had fractures of both legs, and his brother Joshua was also injured; the Rev. Dawson Dane Hather had a severely injured ankle. An American called Tennant was travelling with his wife who suffered a badly fractured upper femur. Mr Fox, a wine and spirit merchant, had a lucky escape. He had been sitting between Mr Blake and John Todhunter, but although he was thrown out of the carriage he only suffered bruised knees and severe shock. Most of the other passengers sustained some form of injury.

Word was immediately sent to Chesterfield and doctors and other assistance arrived quite quickly. The news was also telegraphed to Derby and a special train was immediately sent to Clay Cross containing various officials of the Midland Railway company. Mr Rickman, one of the company directors, was sent to Langley Hall to alert John Meynell’s father, Godfrey, to the accident. Another special train then carried three of the company directors, Godfrey Meynell and Miss Meynell to the site of the accident.

John Meynell was buried at Kirk Langley on May 27th. [2] It is not clear whether his wife Sarah had recovered sufficiently to attend the funeral, since newspaper reports mentioned that she had also been injured. The couple had been married for less than nine years and already had six children, the eldest just seven and the youngest of whom, Francis William, had been baptised only two weeks before the accident.[3] He would grow up to become vicar of Stapenhill.

The now widowed Sarah Brooks Meynell was the daughter of Dr William Brooks Johnson of Coxbench Hall (c.1763-1830) who had been noted for carrying a message of support from Derby to Paris, along with Henry Redhead Yorke in the early days of the French Revolution. Her twin sister, and only sibling, Eleanor Franceys Johnson had died of consumption in 1842, and their mother a year later, leaving Sarah Brooks Meynell as heir to Coxbench Hall among other property.[4] [5] Ultimately she clearly made a good recovery from her injuries since she lived until 1890, dying on 18 December aged seventy-four.[6]

The only response of the railway company to the accident was to forbid train drivers from making unscheduled stops to set passengers down at closed stations.

[1] Leeds Intelligencer. (1851) Dreadful Accident on the Midland Railway. Leeds Intelligencer. 24 May 1851. p.8a. http:www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk : accessed 26 June 2017.

[2] Burials (PR) England., Kirk Langley, Derbyshire. 27 May 1851. MEYNELL, John. Ancestry. Collection: Derbyshire, England, Church of England Burials, 1813-1991. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 18 October 2017.

[3] Baptisms (PR) England, Brimington, Derbyshire. 04 May 1851. MEYNELL, Francis William. Ancestry. Collection: England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 18 October 2017.

[4] Deaths (CR) England., Holbrook, Derbyshire. RD: Belper. 1st Qtr 1842. JOHNSON, Eleanor Franceys. Vol. 19. p.350. No.477.

[5] Derbyshire Courier (1843), Derbyshire Courier. Saturday 04 February 1843. p.3f. http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk : accessed 19 October 2017.

[6] Testamentary records. England. 16 February 1891. MEYNELL, Sarah Brooks. Principal Probate Registry. Calendar of the grants of probate. p. 301. Collection: England & Wales, National Probate Calendar, 1858-1966. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 19 October 2017.