Photo by Colin Smith via Wikimedia Commons

When you hit a brick wall with one of your ancestors it can be helpful to write down their story as if you are telling it to an interested family member. By recording the facts you do have, together with the sources for them, you can be sure of what you know, and by making clear where the blanks are it will help you decide where to look for the answers.

Here then is my current mystery – my four times great grandmother Anne Coperthwaite[1] who married Henry Weston in 1747 when she was nineteen and he was almost seventy.

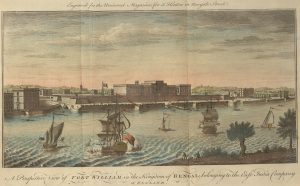

I have written before about Henry’s adventurous sister Judith Weston who travelled to India in search of a husband. Their father John Weston of Ockham in Surrey had fallen on hard times, having become hugely indebted as a collector of taxes under Queen Anne, and been compelled to sell off the family estates in 1710. [2] Henry gradually rebuilt the family fortunes and inherited valuable legacies from his friends Sir William Perkins of Chertsey (died 1741), from his brother Matthew Perkins (died 1749), and from William Nicholas (died 1750).

So, when Henry married Anne he was already wealthy and soon to be much more so. He was described as being ‘of Chertsey’ on the marriage licence, which also indicated that Anne was marrying ‘with the Consent of John Brown her Guardian appointed by the High Court of Chancery’.[3] The licence recorded that Henry was aged fifty and upwards, but in fact he was probably baptised on 21 November 1678,[4] making him about sixty-nine – fifty years older than Anne!

There may be two possible explanations for the marriage – either Henry was marrying in order to acquire further estates, or he was marrying to protect Anne and her property (perhaps at the request of her natural father) since she could reasonably have been expected to outlive Henry and she or her children would then inherit all his estates. Both could of course have been possible, as could genuine affection between Anne and Henry.

So what do we know about Anne?

I have not found a record of her baptism but when her mother Jane Coperthwaite made her Will soon after Anne’s birth, and shortly before her own death in 1727, she ensured that her property and the lands she owned in Kent were protected for her daughter.[5] On the basis of Jane’s Will and the date of Anne’s marriage licence, I calculate that Anne was probably born between 26 March and 16 May 1727.

Although her burial record refers to her as Mrs Jane Coperthwaite it also records her as a spinster, so ‘Mrs’ was a courtesy title indicating her social and economic, rather than her marital, status. [6] At the time Jane was probably thirty-nine as there is a baptism at St Andrew’s Holborn on 19 December 1687. Her father was John Coperthwaite and her mother Jane Brodnax. The Kentish property that Anne inherited had come to Jane through the Brodnax family of Godmersham (who, incidentally, were later connected to the family of Jane Austen, but that’s another story).

So Anne’s mother was independently relatively wealthy, and might have been more so for it appears that her uncle Matthew Coperthwaite, Gentleman of the parish of St James, Westminster, probably cut her out of his Will (written in February 1727) on hearing of her pregnancy. He left her ‘one shilling and no more in full satisfaction and Bar of all demands’, but left £500 a year to her only sister Elizabeth.

Perhaps it is on the basis of the legacy of West Horsley to Henry Weston, that it has been assumed that William Nicholas must have been the father of Jane Coperthwaite’s daughter Anne. However, the Will was not a random legacy to a friend, for William and Henry were distantly related by marriage and importantly the transfer of West Horsley was effectively a sale that funded the many legacies left by William to relatives, servants and charity.

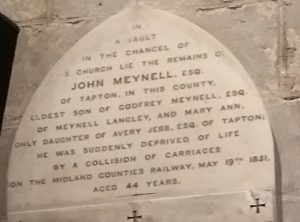

Having no male heirs himself, William left various properties to the heirs of his grandfather Sir Edward Nicholas (1593-1669). This explains the inclusion of Sir John Abdy (also an executor) whose grandmother was a granddaughter of Sir Edward Nicholas. The Will left property at Winterbourne Gunner and Bishop Cummings to Sir John Abdy, and William’s London house at Old Spring Gardens in St Martin in the Fields, London to his Compton nephews and niece (children of his sister Penelope Nicholas).

In total a large number of cash legacies came to over £4,600 and it appears that this was mainly funded by the transfer of the West Horsley estate and house to Henry Weston in return for a payment of £4,000, (which was equivalent to an income value of about £10.5 million at 2020 values) [7]. Henry also received a gold cup and cover, a valuable personal bequest.

William’s executors were Sir John Abdy and Richard Turner a London physician who received £1,000 of Million Bank Stock (effectively lottery tickets).[8] The two executors were also the residuary legatees.

Typical of the network of associations of their social class, Henry Weston was not simply a friend or business associate of William Nicholas. His aunt Katherine Weston was the first wife of Sir Richard Heath whose grandson (another Richard Heath, whose son Nicholas received £1,000) married Bridget Nicholas, daughter of William’s brother John Nicholas.

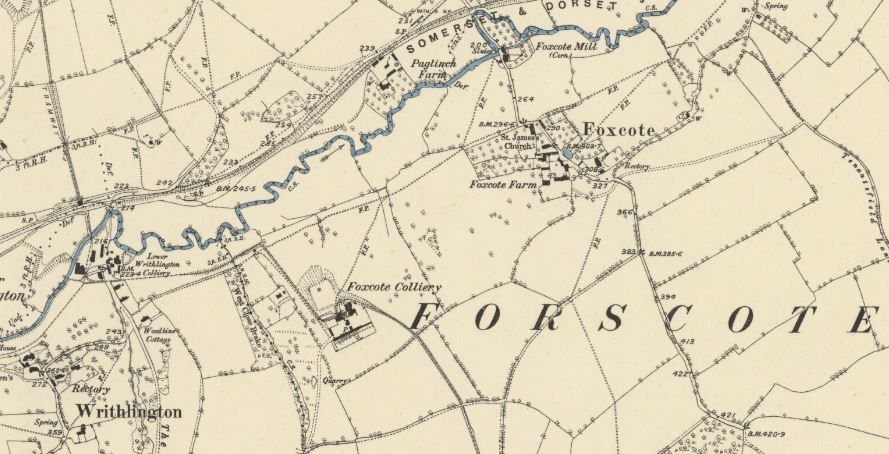

I have found nothing to indicate how Jane Coperthwaite might have met William Nicholas, but she was buried at Weybridge which is only about 12 miles from West Horsley, and implies she was probably living in the area and so could have known both John and William Nicholas. Chertsey where Anne Coperthwaite and Henry Weston were both living in 1747 is even closer to Weybridge. Jane’s mother and sister were later buried in the Brodnax family vault at Godmersham although Elizabeth was living in the parish of St George the Martyr, Holborn when she wrote her Will in 1738 just over a year after the death of her mother.[9] [10]

I have not been able to find a Will for Anne Coperthwaite’s grandmother Jane, nor her grandfather John Coperthwaite. Both were involved in various legal disputes relating to issues of property and inheritance and hence may be assumed to have been well to do. Indeed, a John Coperthwaite, almost certainly this one, stood recognisance for William Hussey of Highworth who was indicted for murder in 1688 and convicted as an accessory, having been present at the fatal brawl. He was later reprieved, but ‘John Copperthwaite of St. Andrew’s Holborn gentleman’ was one of several who put up £500 as security before the trial. [11]

So having found out something about the protagonists in this mystery, we are left with a crucial unanswered question. As William Nicholas was unmarried and had no heir, why would he not have married Jane Coperthwaite on learning of her pregnancy, if he was indeed the father of her child?

Was there some unresolved and implacable family opposition relating to the sides taken by the two families during the Civil War? It’s not impossible.

On the other hand, might the father of Anne Coperthwaite have been William’s married brother John Nicholas (1663-1742) from whom William inherited West Horsley?

William Nicholas in his Will seems to have been tying up a lot of loose ends, perhaps the arrangement with Henry Weston after his marriage to Anne was just another attempt to do the right thing by the family.

This is not a mystery that is ever likely to be solved, but if it was not someone else entirely, on balance I would put my money on John, not William, Nicholas as the father of Anne Coperthwaite.

Sometimes in family history research you just have to accept there may be no answer to your brick wall question, but it’s always worth looking.

Sadly Anne died in childbirth after the birth of her second child Henry Perkins Weston and, incidentally, if you think you recognise the Nicholas/Weston property of West Horsley Place it has featured in a number of TV and film productions, notably the BBC comedy Ghosts.

[1] There are a great many variants of the name Coperthwaite, including Copperthwaite, Copperthwayte, Copperwait, Copperwite and Cowperthwaite. Generally, the family seem to have favoured Coperthwaite.

[2] http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1660-1690/member/weston-john-1651-1712

[3] Faculty Office Marriage Licences. England., 20 March 1746/47. WESTON, Henry and COPPERTHWAYTE, Anne. Society of Genealogists, London.

[4] Baptisms (PR) England, All Saints, Ockham. 21 November 1678. WESTON, Henry. Ancestry Collection: Surrey, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812. Image No:17. http://www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 31 October 2017.

[5] Testamentary records. England., 11 July 1727. COPERTHWAITE, Jane. Will. Prerogative Court of Canterbury: Will Registers. PROB 11/616/214. The National Archives, Kew, England. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D631632 : accessed 30 December 2022.

[6] Burials (PR) England, Weybridge, St James. 01 July 1727. COPERTHWAITE, Mrs Jane. Surrey Burials. 2384/1/2. https://www.findmypast.co.uk : accessed 17 December 2022.

[7] Testamentary records. England., 10 August 1749. NICHOLAS, William. Will. Prerogative Court of Canterbury: Will Registers. PROB 11/776/158. The National Archives, Kew, England. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D3378139: accessed 17 January 2023. and www.measuringworth.com

[8] Possibly Richard Woodroofe Turner, son of Daniel and Isabella Turner, baptised 12 November 1693 at St Ann Soho. This would suggest a possible relationship to the Heath family as the second wife of Sir Richard Heath was Lettice Woodroffe.

[9] Burials (PR) England, Godmersham, St Lawrence, Kent. 04 January 1736/37. COPERTHWAITE, Mrs Jane. Canterbury Cathedral Archives U3/117/1/2. https://www.findmypast.co.uk : accessed 02 January 2023.

[10] Burials (PR) England, Godmersham, Kent. 27 March 1739. COPERTHWAITE, Elizabeth. Find My Past [Transcription]. England Deaths & Burials 1538-1991. https://www.findmypast.co.uk : accessed 10 January 2023.

[11] British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/middx-county-records/vol4/pp321-328 [accessed 3 January 2023].